I must have mapped out the ocean’s physical properties for over a dozen terminating glaciers and each one is unique and leaves me in complete awe. Really, they are fascinating and I suggest you create the opportunity to see one in your lifetime. They are slow-moving frozen rivers comprising not just melting water but discharging nutrients as well. Starting in 2015, I started noticing what Matt called “Narwhal vomit” floating by during our studies of the melting glaciers. There would be sea grasses, kelps and jellies afloat. Just whip together a blend of seasonal atmospheric and oceanographic physical dynamics, while sunlight gets its chance to pierce a freshly uncovered sea surface, and then top it all off with a deluge of nutrients (iron/nitrogen rich) from the glacial grind down the mountain sides into the drink, and what do you get? You may find yourself surrounded by a disgusting new phenomena: high Arctic algal plankton bloom. Remember, there are two plankton types: phyto (plant-based) and zoo (animal) plankton.

When we approached Croker Bay and worked our way up to the glaciers, there was the most incredible display of white silly string-looking, spitty, gooey, bubbly, yellow gunk spread all over the sea surface and visible at depth as we occupied each CTD station. The sun was reflecting off this stuff not just at the surface but in the photic layer (a layer defining as far as the light can reach) and each sun beam was reflecting back off of the plankton causing the ocean color to appear to be a Caribbean teal color. Not only were we capturing the physical oceanographic warm current in Croker Bay but also the very physical characteristics that relate to an incredible plankton bloom unfolding around us before our very eyes. It is difficult to say something about the health of an ocean ecosystem without first understanding the shape of the ocean basin, then the temporal (over time) and spatial specifics of the physical dynamics (currents, temperature, salinity).

When we approached Croker Bay and worked our way up to the glaciers, there was the most incredible display of white silly string-looking, spitty, gooey, bubbly, yellow gunk spread all over the sea surface and visible at depth as we occupied each CTD station. The sun was reflecting off this stuff not just at the surface but in the photic layer (a layer defining as far as the light can reach) and each sun beam was reflecting back off of the plankton causing the ocean color to appear to be a Caribbean teal color. Not only were we capturing the physical oceanographic warm current in Croker Bay but also the very physical characteristics that relate to an incredible plankton bloom unfolding around us before our very eyes. It is difficult to say something about the health of an ocean ecosystem without first understanding the shape of the ocean basin, then the temporal (over time) and spatial specifics of the physical dynamics (currents, temperature, salinity).

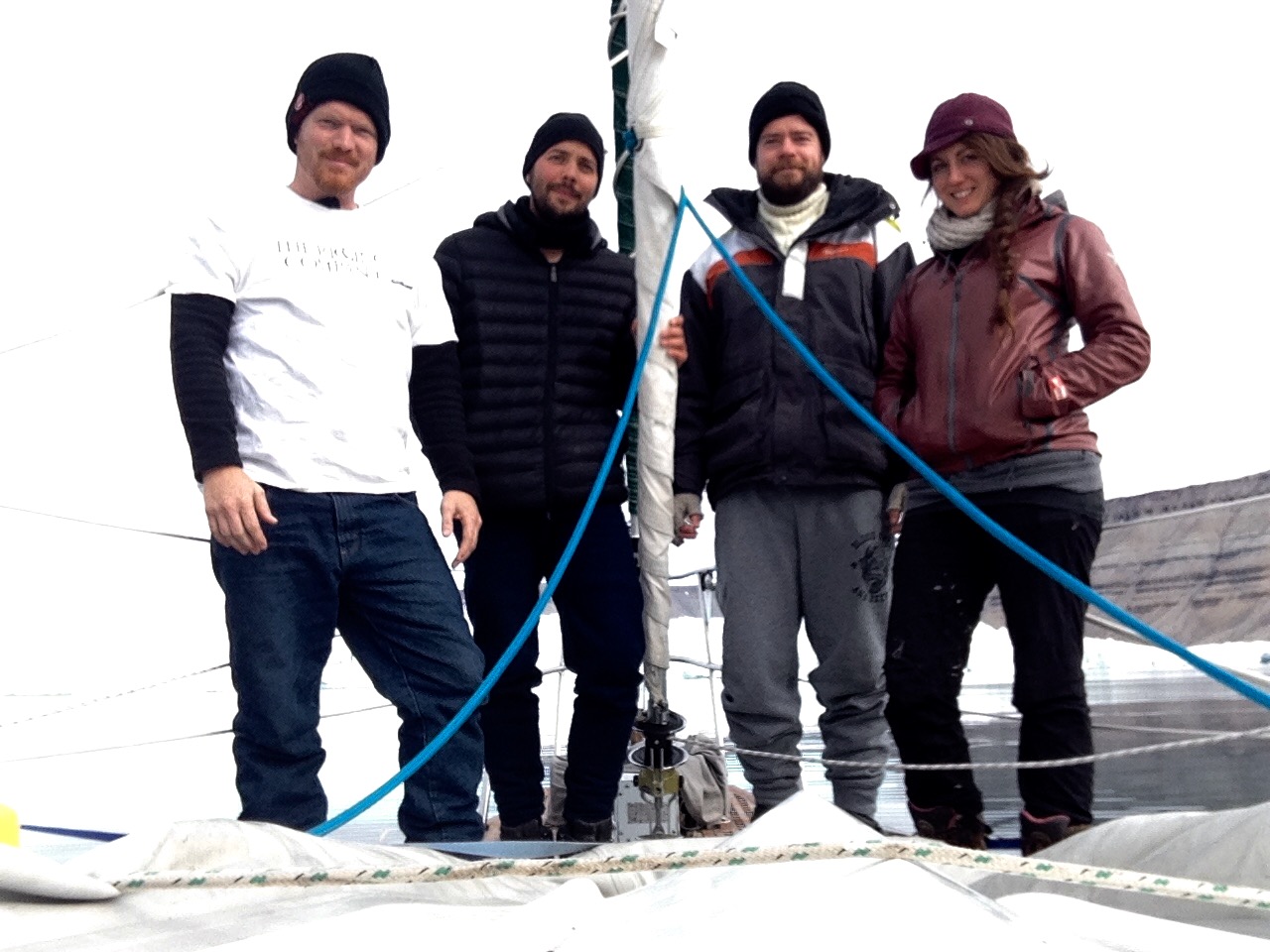

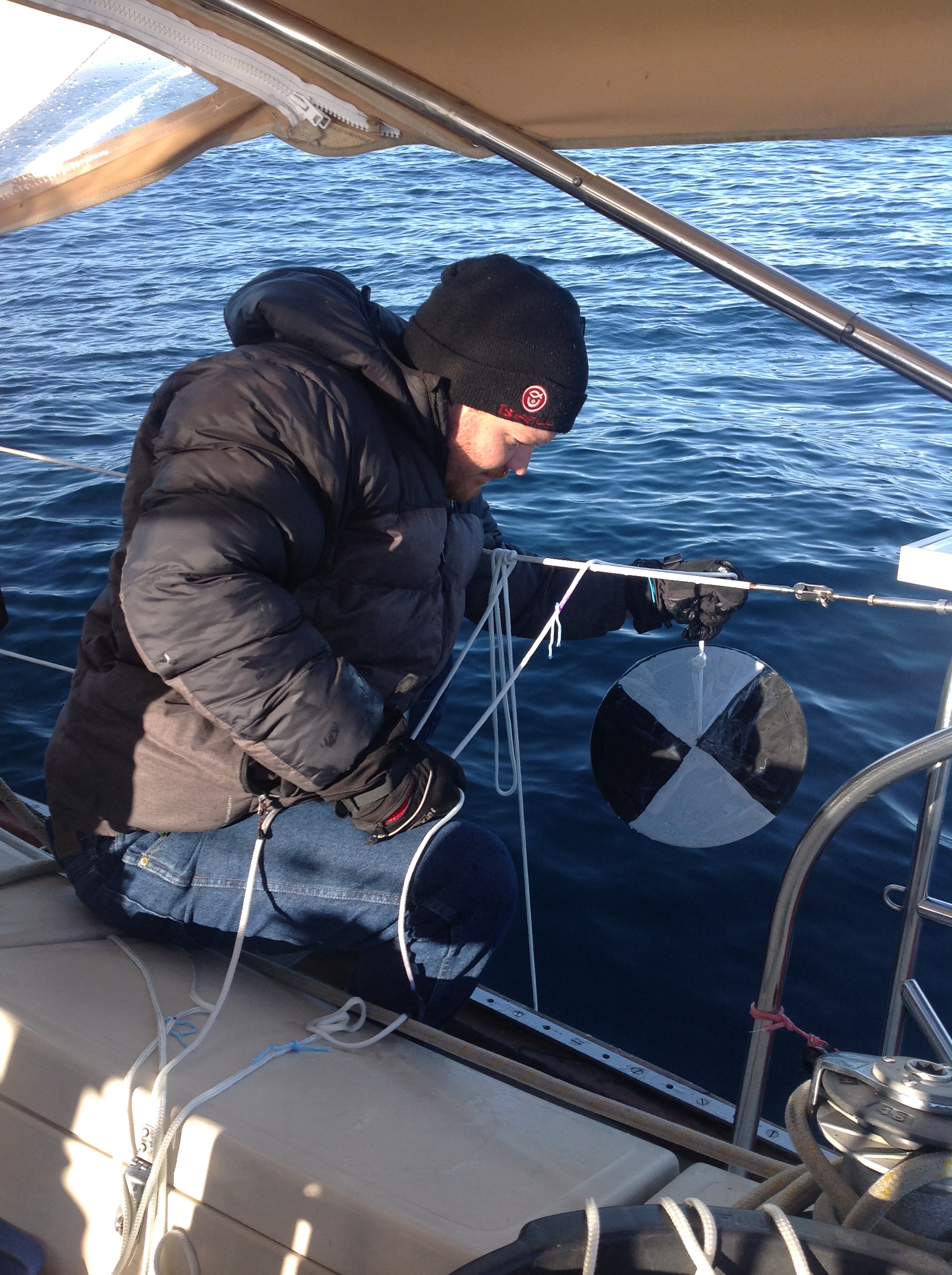

I do not get tired of seeing the wildlife but boy were Matt and I startled when we thought we heard a polar bear during our pre-drone flight checks while sitting aside Croker North glacier. We were discussing the test flights goals for our Phantom 4 Near Infrared (NIR) Scanning Drone and heard growling nearby, on and off. The red spectrum wavelengths are known to best capture evidence of chlorophyll from satellites so perhaps this camera could detect the ongoing plankton bloom downstream of turbid glacial discharge waters for Chlorophyll and discharge turbidity plumes signals. We kept a shotgun nearby during the test to protect ourselves in the event of a charging hungry polar bear. As an early career polar scientist I have limited access to scientific equipment needed to best observe the biogeochemical information needed to relate to the physical oceanographic properties. Any sample I would have grabbed of plankton and a measurable Chlorophyll concentration would surely decompose without storage needs met. So the NIR drone, pictures, the use of a sechhi disk and a handheld spectrometer would be my only way to capture the biologic phenomena. Looks like I may have to return to Croker Bay to get the full biogeochemical story to assess the health of this unique ocean environment, and next time I will have the tools needed to tie the melt season tidal glacial ecosystem together.

secchi disk

It’s getting pretty late in the summer and the NW Passage has not opened yet at the pinch point to allow us to gun it and make some miles. Crew morale teetered on that fact, and the plankton bloom dwindles as we determine if we should head to the nearest town Pond Inlet, some 120 miles or so away to top off fuel and water. Gossip in the anchorage revealed that some sailboats bound for the Passage are turning back while others have already started to attempt to have a go at the ice-jammed path. Either way the Coast Guard has announced that they will not help break sailors free and to safe refuge.

On the Alaska side of the NW Passage, two young brave girls Talia (12) and Savai (9) keep busy aboard their family sailboat called Dogbark. Unlike us they are heading from West to East they also had been waiting behind a small island for ice to clear for them to continue east. Talia and Savai are doing some reconnaissance observations for the Ocean Research Project. They are in charge of taking notes twice a day on oceanographic, meteorological, ice conditions and ocean turbidity. Their key notes are a great way to gauge the potential for plankton bloom conditions. Check out their site.

When the skies clear I take in a noon site: an ocean color reading just as the polar satellites are passing overhead. I use a handheld spectrometer that measures the projected light off the ocean surface. Certain color values will indeed point to a chlorophyll concentration that can be later compared to what the satellites are reading. I must say, I have rarely had the chance to “groundtruth” the ocean color while cloudy days persist or partly cloudy days with low-lying, fast-moving fog bands would certainly lead to inaccurate readings. Knowing how many clear sky noon days the Dogbark girls record will help me define the opportunity of groundtruth days across more of the NW Passage. In the meantime, I can grab a depth value from my sechhi disc, a black and white circular plate lowered off the boat foot by foot until it disappears into ocean darkness. This value will show me just how deep the light can reach before the wavelengths are absorbed. It will quantify the turbidity (dirtiness) of the water. My CTD data also shows me a depth in the salinity and temperature profile where the mixed layer is, which is closely related to the deep maximum limit for Chlorophyll production. This is a trend I can tease out of the dataset from our offshore Baffin Bay CTD cast stations and all the way up the glacier face.

Toboggan had a few hard mornings of getting hit by small pack ice floes while on anchor, then dodging and pushing ice floes away from our boat with our dinghy. It was a hard fact to swallow but Toboggan is not prepared to over-winter frozen in the ice at any refuge towns en route. There is no guarantee Toboggan can even make it to another town past the pinch point of Bellot Strait without getting frozen in. A warm winter this year has created a cold summer. Where older ice further North broke off and flooded the usual passage clearings to no end. A few other boats plan to push through but Toboggan and Dogbark and many others decide to head south. Matt and I made our plans to return to the states and although we have the longing to have journeyed through the passage, we know that the data collected is incredibly powerful in relaying the conditions that spurred an unusual mid-summer plankton bloom and the ocean warming influence present. This is my third summer in the Arctic, sailing the same region around the same time, andno two years are identical. Back to school I go, like you, to make sense of our observations and investigate the story they tell. Here explains the conditions of the Arctic this year as opposed to previous.

Cheers,

Nicole